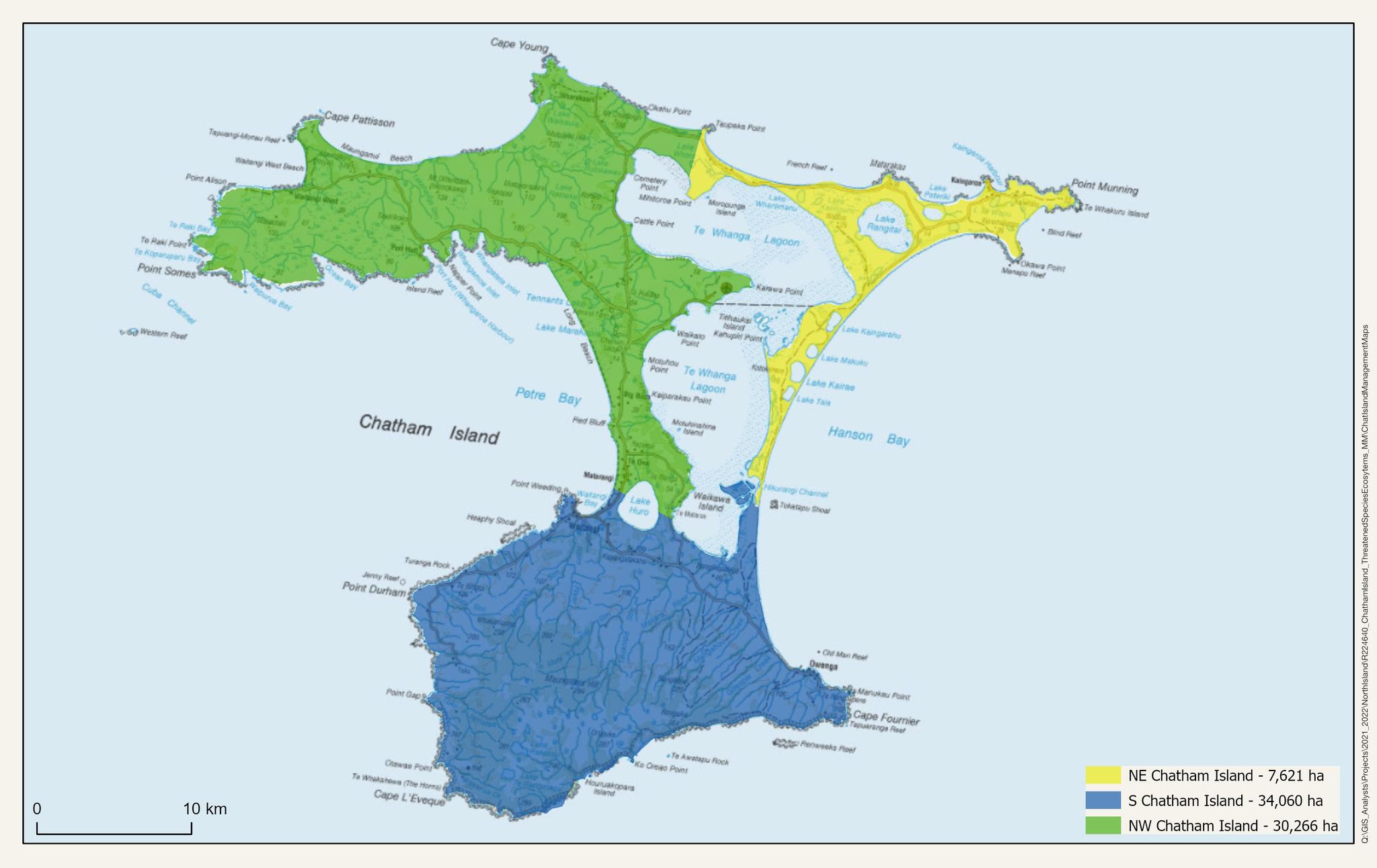

The yellow north-eastern section is the first target of Predator Free Chathams

I have visited Aotearoa New Zealand on seven occasions between 1988 and 2017 from my home in South Africa to attend conferences, workshops and ACAP meetings, and once on sabbatical. On these trips I have arranged things to find the time to visit no less than 11 of New Zealand’s offshore and sub-Antarctic islands to view seabird colonies and to gain first-hand experience of restoration efforts to remove introduced predators. In a truly ambitious effort, Predator Free 2050, aims to achieve the New Zealand Government’s goal of eradicating Common Brushtail Possums Trichosurus vulpecula, mustelids (Stoats Mustela erminea, Ferrets M. furo and Weasels M. nivalis) and rats (Norway Rattus norvegicus, Black or Ship R. rattus and Kiore or Polynesian R. exulans) by 2050 across the whole country. Feral cats Felis catus are not a target species. Predator Free 2050 has led to the establishment of many local environmental trusts (with some including feral cats as targets) and the development of innovative trapping equipment and methods,

In this ACAP Monthly Missive I highlight activities or plans by trusts to rid three of New Zeaaland’s largest offshore islands, all inhabited, of their introduced predators. Two of them, Great Barrier and Stewart, I have visited, the third, the Chatham Islands, I have not (but of course would like to).

Great Barrier Island

A Black Petrel pair in the monitoring colony on Hirakimatā or Mount Hobson, Great Barrier Island, photograph by ‘Biz’ Bell

Following my attendance at the 10th Meeting of the ACAP Advisory Committee (AC10), held in Wellington September 2017, I flew to Auckland and then by small plane to Great Barrier Island (Aotea) on the edge of the Hauraki Gulf. Once there I hiked the three-day Aotea Track staying overnight in Department of Conservation field huts to visit the main breeding site of the Vulnerable Black Petrel Procellaria parkinsoni on Mount Hobson (Hirakimatā). Unfortunately, my visit was outside the summer breeding season, but I took note of the many numbered burrows among the tree roots and the traps set for introduced predators on the upper slopes of Mount Hobson, the island’s highest peak.

A view of 627-m Mount Hobson from the Aotea Track, home of the ACAP-listed Black Petrel

Great Barrier Island is fortunately free of free of Possums, Stoats, Weasels and Norway Rats (and European Hedgehogs Erinaceus europaeus, feral goats and deer). It does support feral cats, feral pigs (of which I saw evidence of their rooting), Black Rats, Kiore and House Mice Mus musculus. My host before and after the hike told me he regularly put out food for two feral cats that visited his kitchen door – and did not seem to be that concerned of their likely depredations of the island’s native fauna.

Great Barrier Island inhabitants now support eradicating the island’s introduced predators, photograph from Tū Mai Taonga

However, it seems things have changed in the seven years since my visit with the attitudes of the c. 1000 inhabitants (click here for a video). The Aotea Great Barrier Island Environmental Trust and the Ngāti Rehua Ngātiwai ki Aotea Trust with support from the Department of Conservation as part of the Predator Free 2050 project are working via a large-scale project called Tū Mai Taonga towards eradicating feral cats and rats from the 28 000-ha Island, to allow the return of native birds that have become locally extinct (click here for a 2022 project report). I would love to hike the Aotea Track again after the cats and rats have gone; but unrealistic really, as I head towards my ninth decade.

Stewart and Ulva Islands

Ulva Island from the air

In February 2010 I attended a conference on Island Invasives: Eradication and Management, held at the University of Auckland. Once the meeting was over, I flew to Invercargill at the bottom of South Island and then took the ferry across the Foveaux Strait to Stewart Island (Rakiura), New Zealand’s third largest island at 174 600 ha. My purpose was to visit Ulva Island/Te Wharawhara, a Department of Conservation open sanctuary that is part of the Rakiura National Park. Although Ulva does not support breeding seabirds I wanted to visit an island that had been cleared of its Norway Rats, as it was in 1997. As well as appreciating the resurgent bird song, and an inquisitive Stewart Island Weka Gallirallus australis scotti that run up after my sandwiches (I did not feed it), I noticed the many rodent traps spaced around the island, kept ready in case of reinvasions (Ulva is only 780 m off Stewart Island, well within the reach of swimming Norway Rats).

After my lunch! A Stewart Island Weka, photograph from Wikimedia Commons

Incursions of Ulva by rodents have occurred at least 20 times. In August 2023 following signs of rats, the rodenticide brodifacoum was aerially dispersed over the island’s 267 hectares. A previous aerial bait drop occurred in August 2011 in response to a December 2010 rat incursion when a breeding population became established. The island was declared rodent free in March 2024 after a dead rat was found in a trap in February and a month-long incursion response with detection dogs, trapping and trail cameras. The island is co-managed with Department of Conservation by the Ulva Island Charitable Trust, which funds an annual bird survey.“Tiakina Te Wharawhara” - a guide to protecting Ulva Island produced by children of Stewart Island's Halfmoon Bay School in 2020

Keeping Ulva Island rodent free will continue to be a challenge as long as rats are present on Stewart Island. The Rakiura Community & Environment Trust (SIRCET) was founded in 2002 to promote projects that benefit the Stewart Island/Rakiura community and its environment. Its focus is predominantly ecological restoration through control of pests and weeds and planting. The Predator Free Rakiura trust, according to its website, will tackle predator removal in stages, with each step informing the design of the next. The first stage is expected to begin in 2025 with a 10 000-ha block at the southern end of the island where the aim will be to remove Possums, feral cats, rats and Hedgehogs. Stoats, Weasels, Ferrets, House Mice, pigs and goats are not present on Rakiura. Deer and domestic pet cats are not targets for removal.

Although I did not see any procellariiform seabirds ashore on my short visit to Stewart Island, removing Rakiura’s alien predators will surely help its land birds, as it has on Ulva.

Chatham Islands

Chatham Albatross chicks on their plastic bucket nests at the Point Gap translocation site; the birds with yellow bills are adult decoys. Photograph from the Chatham Island Taiko Trust

Predator Free Chathams is a community-driven conservation project that aims to eliminate five tintroduced predators (Possums, three species of rats. and feral cats) from the main Chatham Island (71 947 ha), also known as Rēkohu (Moriori) and Wharekauri (te reo Māori). The project is commencing in the 7621-ha north-east (the yellow area on the above map) with the establishment of a trapping network. The project notes that “In the Chatham Islands we’re lucky not have some of the other introduced pests that are causing havoc on mainland New Zealand. For example, mustelids like ferrets, stoats and weasels were never introduced here. We also don’t have non-predator introduced species like deer and rabbits, which also damage native ecosystems.” The introduced feral pigs are stated as not being a target for Predator Free Chathams.

Procellariiform seabirds that breed on the main Chatham Island and would thus benefit from the actions of Predator Free Chathams include the rare and Critically Endangered Magenta Petrel or Taiko Pterodroma magentae, the conservation target of the Chatham Taiko Trust. In 2006 the Trust built an 800-m predator proof fence protecting 2.4 ha of forest to create a secure breeding site for Taiko. Known as Sweetwater, it is now occupied by a small but growing population of the petrel. The Vulnerable Chatham Islands Petrel P. axillarish also breeds on the main island within the Sweetwater Conservation Covenant. It also breeds on nearby Pitt Island (Rangiaotea).

The late David Crockett who rediscovered the Magenta Petrel, then thought to be extinct (and whom I had the pleasure of meeting at a 1982 conference)

An attempt was made to create a new colony of Vulnerable Chatham Albatrosses Thal assarche eremita on Main Chatham by translocating nearly 300 chicks over five years over 2014 to 2018 from the species’ sole breeding locality on the Pyramid to a protected site at Point Gap. So far, it appears to have been unsuccessful, given the lack of reports of any juveniles returning to the site following their fledging from it.

I remain inspired with what New Zealand is trying to do. It is a part pf the world I have grown to appreciate; I wish it well, and the best of luck, as it works towards becoming a predator-free country.

I am grateful to Nigel and Claudia Adams, Biz Bell, Lloyd Davis, Paul Dingwall, Chris Gaskin, David Hemmings, Peter McClelland, Chris Robertson, Dick Veitch and Susan Waugh who facilitated my visits to seabird colonies and islands by variously providing advice, accommodation, transport and guidance during my visits to New Zealand. Apologies to anyone left out due to a fading memory.

John Cooper, Emeritus Information Officer, Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, 06 January 2025

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español