Albatrosses (but much more rarely petrels) have appeared in poetry, as featured in ACAP Latest News from time to time. Leaving aside the scientific and conservation papers and reports regularly covered in ALN and also children’s books (click here), albatrosses have also appeared in fictional prose literature.

In Chapter 42 entitled “The Whiteness of the Whale” in Herman Melville’s 1851 Romantic novel Moby-Dick; or, The Whale, Ishmael, the book’s narrator, muses over the significance and symbolism of the colour white, alluding to that most famous poem featuring an albatross, Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Melville had gone to sea on a whaler for a year and a half as a “green hand” in 1840. He most likely then encountered albatrosses when his ship rounded Cape Horn into the Pacific, giving him a personal experience (unlike Coleridge's) to influence his later writings.

According to one reviewer (click here): “Manifested perfectly in this chapter, Melville presents the purest of all symbols — the color white –, and transvalues it to represent the epitome of evil, fear, and malice.” Read the extract below to gain your own opinion.

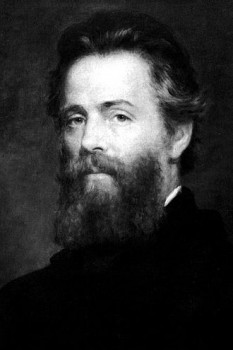

Herman Melville, 1819-1891

“Bethink thee of the albatross, whence come those clouds of spiritual wonderment and pale dread, in which that white phantom sails in all imaginations? Not Coleridge first threw that spell; but God's great, unflattering laureate, Nature.*

*I remember the first albatross I ever saw. It was during a prolonged gale, in waters hard upon the Antarctic seas. From my forenoon watch below, I ascended to the overclouded deck; and there, dashed upon the main hatches, I saw a regal, feathery thing of unspotted whiteness, and with a hooked, Roman bill sublime. At intervals, it arched forth its vast archangel wings, as if to embrace some holy ark. Wondrous flutterings and throbbings shook it. Though bodily unharmed, it uttered cries, as some king's ghost in supernatural distress. Through its inexpressible, strange eyes, methought I peeped to secrets which took hold of God. As Abraham before the angels, I bowed myself; the white thing was so white, its wings so wide, and in those for ever exiled waters, I had lost the miserable warping memories of traditions and of towns. Long I gazed at that prodigy of plumage. I cannot tell, can only hint, the things that darted through me then. But at last I awoke; and turning, asked a sailor what bird was this. A goney, he replied. Goney! never had heard that name before; is it conceivable that this glorious thing is utterly unknown to men ashore! never! But some time after, I learned that goney was some seaman's name for albatross. So that by no possibility could Coleridge's wild Rhyme have had aught to do with those mystical impressions which were mine, when I saw that bird upon our deck. For neither had I then read the Rhyme, nor knew the bird to be an albatross. Yet, in saying this, I do but indirectly burnish a little brighter the noble merit of the poem and the poet.

I assert, then, that in the wondrous bodily whiteness of the bird chiefly lurks the secret of the spell; a truth the more evinced in this, that by a solecism of terms there are birds called grey albatrosses; and these I have frequently seen, but never with such emotions as when I beheld the Antarctic fowl.

But how had the mystic thing been caught? Whisper it not, and I will tell; with a treacherous hook and line, as the fowl floated on the sea. At last the Captain made a postman of it; tying a lettered, leathern tally round its neck, with the ship's time and place; and then letting it escape. But I doubt not, that leathern tally, meant for man, was taken off in Heaven, when the white fowl flew to join the wing-folding, the invoking, and adoring cherubim!”

With thanks to Mark Rauzon.

John Cooper, ACAP Information Officer. 10 December 2014

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español