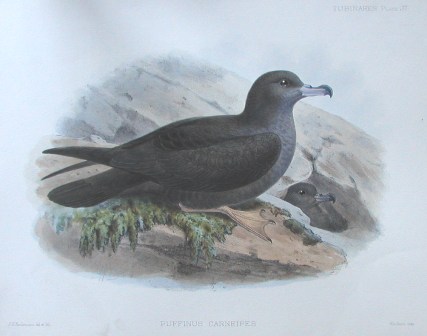

Flesh-footed Shearwater, hand-coloured lithograph by John Gerard Keulemans, from the Monograph of the Petrels (Tubinares), 1907-10, Plate 32, by Frederick du Cane Godman

Alexander Bond (Bird Group, The Natural History Museum, Tring, UK) and Jennifer Lavers have written in the journal Ibis International Journal of Avian Science suggesting a new name for the Near Threatened Flesh-footed Shearwater Ardenna carneipes, noting the bias in equating flesh-coloured with the predominant human skin colour of those that originally assigned the name. They write: “The default assumption that flesh equates with a whiteness reflects a northern European influence and racism”.

The paper’s abstract follows:

“Recently, there has been increased focus on the origins and history of common names for organisms, especially birds. Of particular interest are eponymous common names that reflect our colonial past. While identification of alternative names can be straightforward for some species, for those that migrate across jurisdictions including the lands of multiple Traditional Owner/Indigenous groups, reaching consensus on a single name that reflects the features of the species and their cultural importance can be substantially more complex. Using the migratory Ardenna carneipes as a case study, we propose a new common name (Sable Shearwater) for the species and discuss the many challenges that others will need to consider when navigating this important yet sensitive space.”

A previous ACAP Monthly Missive on the sensibilities of retaining eponymous names (e.g. for Buller’s Albatross Thalassarche bulleri) also referred to Ardenna carnepeis, saying:

“As well as wishing to discard all North American eponymous bird names, the OAS Committee has singled out the name of the Flesh-footed Shearwater Ardenna carneipes for special opprobrium, writing that “the word flesh may imply that all - or at least “normal” - skin resembles that of white people. To suggest that the default skin tone is that of a white person is inherently an exclusionary standard”. The committee recommends the epithet “Pale-footed” be used instead. This is of at least potential interest to the Albatross and Petrel Agreement because at a 2019 meeting New Zealand indicated it was considering the merit of nominating the shearwater for ACAP listing, although since then there seems to have been little progress to develop a proposal (click here). New Zealand Birds Online has Pale-footed Shearwater as an alternative name (along with the Maori name Toanui), so this could be seen as a relatively easy change, and one for ACAP to consider adopting.”

If and when ACAP formally considers the shearwater for listing, then it might also wish to consider “Sable Shearwater” as a common name for the species in the English language.

Reference:

Bond, A.L. & Lavers, J.L. 2024. A feathered past: colonial influences on bird naming practices, and a new common name for Ardenna carneipes (Gould 1844). Ibis International Journal of Avian Science doi.org/10.1111/ibi.13356.

John Cooper, Emeritus Information Officer, Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, 05 September 2024, updated 06 September 2024

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español

Seven Heads seawatch point, with Cotton Rock foreground and the Old Head of Kinsale some 12.5 km to the east, photograph by John Lynch

Seven Heads seawatch point, with Cotton Rock foreground and the Old Head of Kinsale some 12.5 km to the east, photograph by John Lynch Figure 1 from the paper: Hake artisanal fishery occurs in the sub-Antarctic channels of Patagonia, Chile. This area comprises three political-administrative regions: Los Lagos, Aysén and Magallanes. The blue box shows the study area, the red circles display where the interviews were conducted, and the yellow rectangles show fishing grounds where we ran the sampling periods related to the offal consumption survey.

Figure 1 from the paper: Hake artisanal fishery occurs in the sub-Antarctic channels of Patagonia, Chile. This area comprises three political-administrative regions: Los Lagos, Aysén and Magallanes. The blue box shows the study area, the red circles display where the interviews were conducted, and the yellow rectangles show fishing grounds where we ran the sampling periods related to the offal consumption survey. Antipodean Albatross by Lea Finke for World Albatross Day 2020, after a photograph by Kirk Zufelt

Antipodean Albatross by Lea Finke for World Albatross Day 2020, after a photograph by Kirk Zufelt