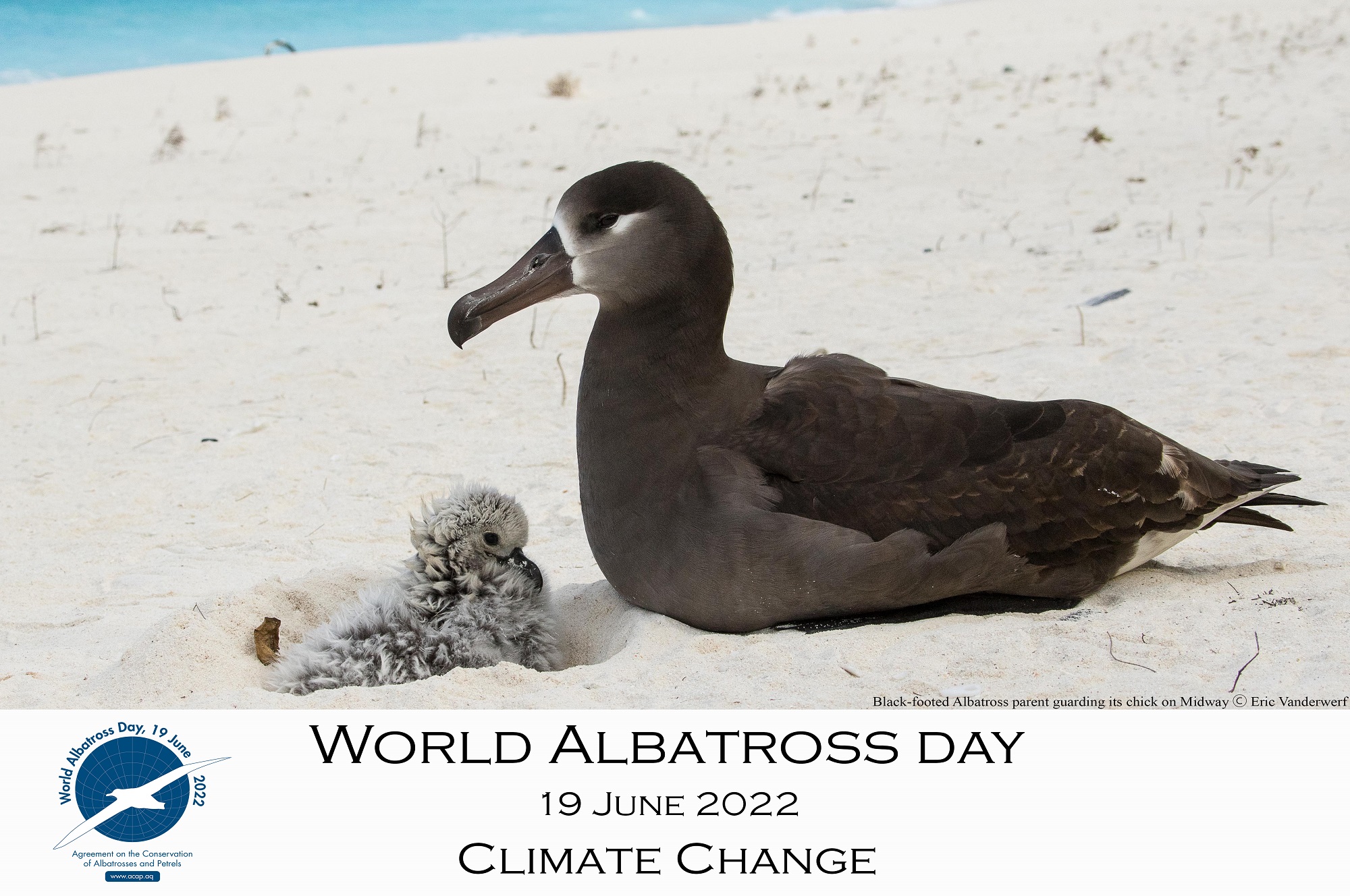

NOTE: The Hawaiian-based environmental NGO Pacific Rim Conservation works to combat the effects of climate change on Hawaii’s procellariform seabirds through its No Net Loss initiative. Two of these species are the ACAP-listed and Near Threatened Black-footed Phoebastria nigripes and Laysan P. immutabilis Albatrosses. With the chosen theme of Climate Change for this year’s World Albatross Day on 19 June, ACAP has been working with Pacific Rim Conservation’s Co-founders, Executive Director Lindsay Young and Director of Science Eric VanderWerf, to commission artworks, produce posters and co-publish infographics that illustrate the deleterious effects of predicted sea level rise and of enhanced storms on the low-lying atolls of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. In their guest post for ‘WADWEEK2022’, Lindsay and Eric describe how translocations are helping secure the futures of these iconic albatrosses and of two other procellariforms in two North Pacific countries.

Safe from sea level rise: Eric VanderWerf and Lindsay Young band a Laysan Albatross on Oahu

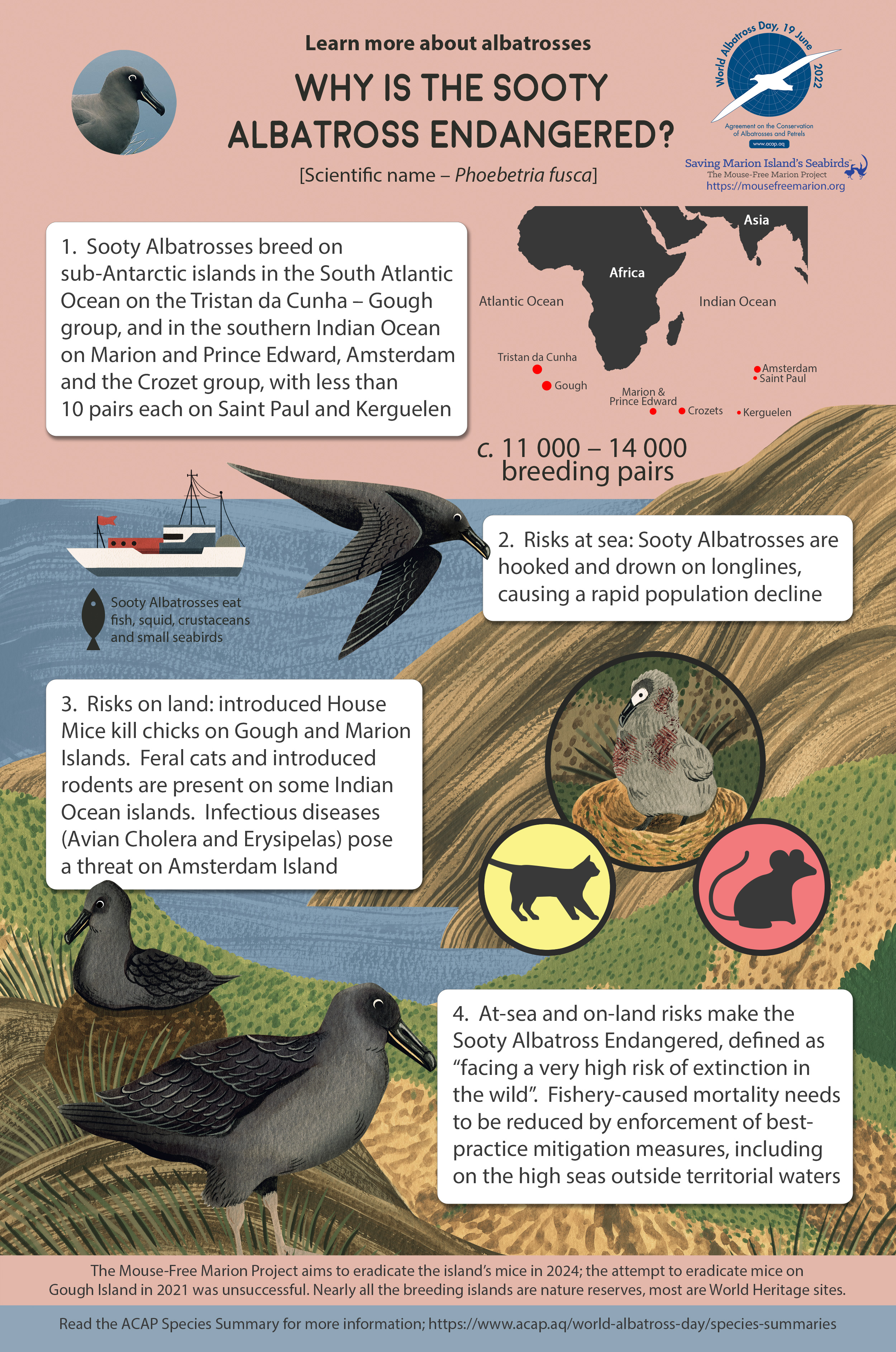

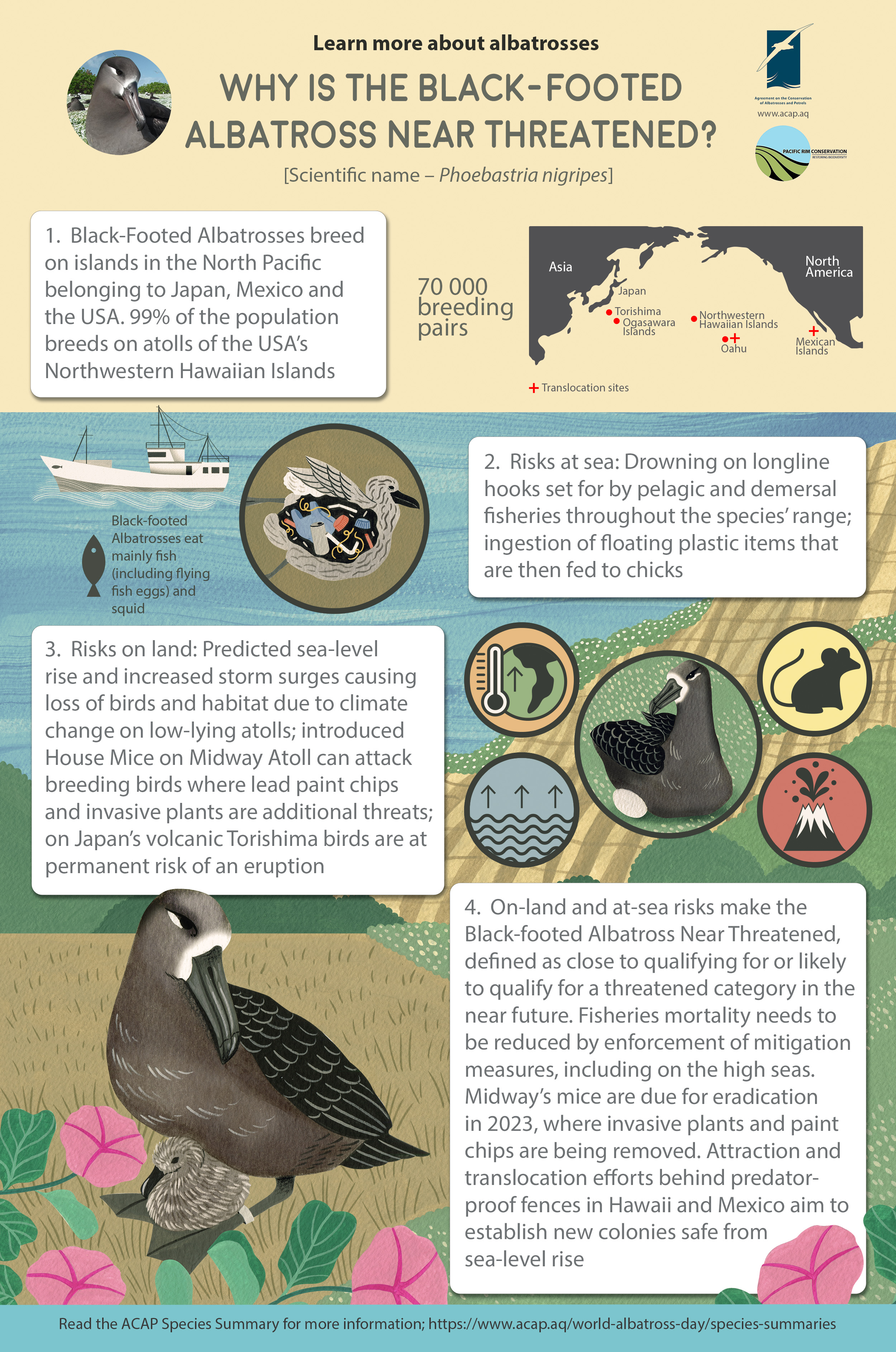

Black-footed Albatross infographic for ACAP and Pacific Rim Conservation by Namasri Niumim

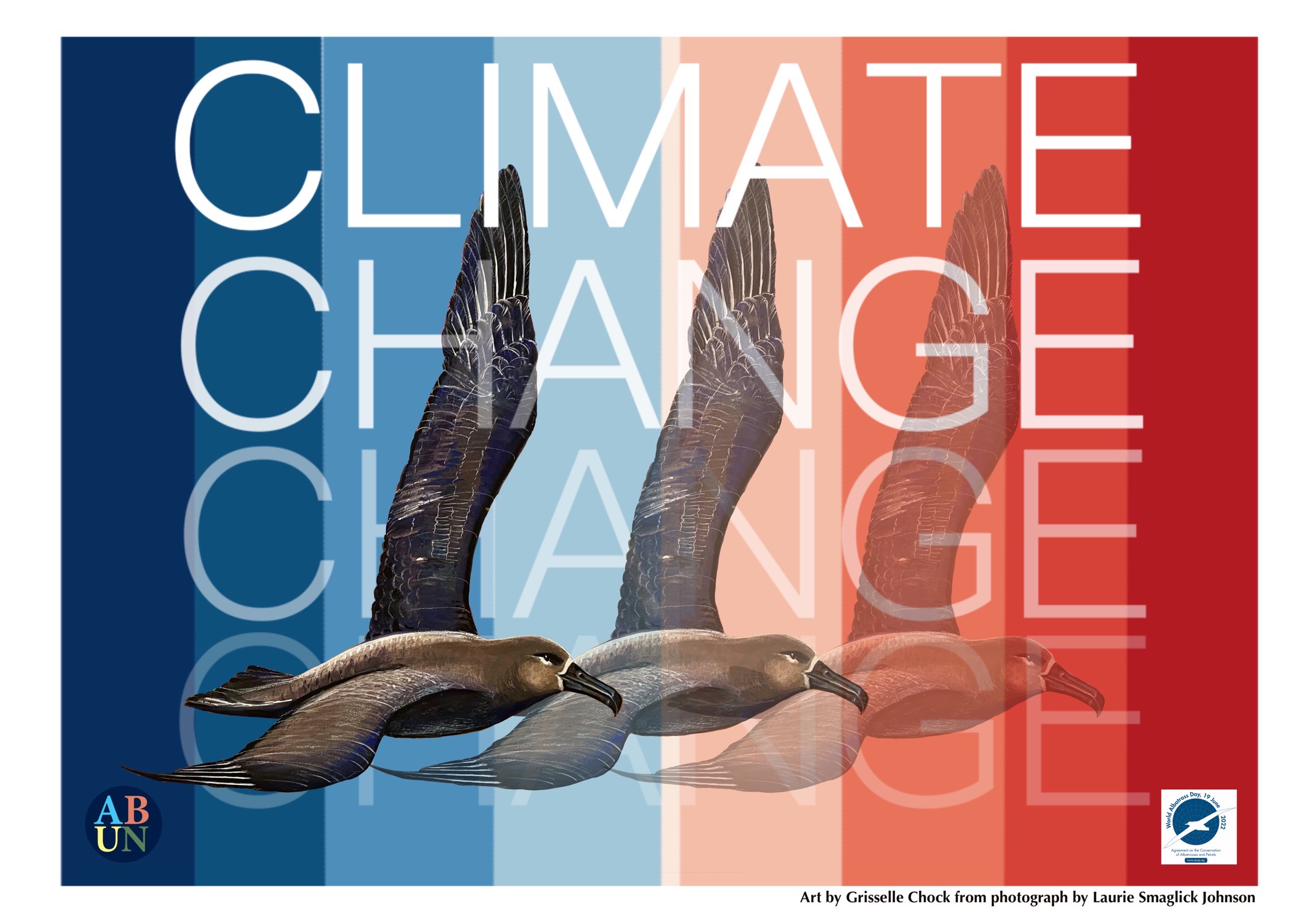

Black-footed Albatrosses fading away in the face of climate change, by Grisselle Chock, Artists and Biologists Unite for Nature

Inundation of Hawaiian seabird breeding colonies caused by sea level rise and storm surge associated with climate change are their most serious long-term threats. Protection of suitable nesting habitat and creation of new colonies on higher islands are among the highest priority conservation actions. The goals of Pacific Rim Conservation’s No Net Loss initiative are twofold:

1) to protect as much seabird nesting habitat in the main islands as is being lost in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands because of the effects of climate change; and

2) to establish new breeding colonies of vulnerable seabird species that are safe from sea level rise and non-native predators.

We do this by building predator exclusion fences, removing invasive predators, and then attracting or translocating birds into these protected areas. We are currently focusing these efforts in the James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge (JCNWR) on the Hawaiian island of Oahu and have begun working on four priority species that are most vulnerable to sea level rise: Black-footed Albatross, Laysan Albatross, Bonin Petrel Pterodroma hypoleuca and Tristram’s Storm Petrel Hydrobates tristrami, all of which have a high proportion of their global populations breeding on a small number of localities only a few metres above sea level.

Visiting Laysan Albatrosses in front of translocated Black-footed Albatross chicks in the James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge

The James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge Translocation Project

From 2015- 2017 we translocated 51 Laysan Albatross chicks (raised from eggs) from the Pacific Missile Range Facility, Barking Sands on Kauai where albatrosses nest close to a runway and are an aircraft collision hazard to the JCNWR. A total of 47 Laysan Albatross chicks successfully fledged as a result of this project, and the first birds started returning as adults to the refuge in 2018. We now have eight Laysan Albatrosses regularly visiting the site from previous translocation cohorts. From 2017-2021 we moved 102 Black-footed Albatross chicks from Midway Atoll and Tern Island, French Frigate Shoals to the JCNWR, of which 97 fledged. Over 2018-2021 we moved 247 Bonin Petrel chicks and 112 Tristram’s Storm Petrel chicks from Midway and Tern Island, of which 246 and 87 fledged, respectively. No Tristram’s Storm Petrels were translocated in 2021 because logistical difficulties and COVID-19 quarantine requirements prevented us from making the collecting trip to Tern Island by ship. In addition, this year we moved 12 of the translocated Bonin Petrel chicks to predator-free Moku Manu Islet a few days before fledging in the hope that they will imprint on the islet and return to it as adults.

A translocated Black-fronted Albatross chick close to fledging in the James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge

A translocated Black-fronted Albatross chick close to fledging in the James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge

In 2019, we saw the first individual Bonin Petrel and Tristram’s Storm Petrel return after just one year. In 2021, we re-sighted returning translocated individuals of all four species, including at least one Black-footed Albatross, 11 Bonin Petrels, eight Laysan Albatrosses and eight Tristram’s Storm Petrels. This season we had two pairs of returning adult Bonin Petrels nest in artificial burrows and successfully fledge chicks. Five others Bonin Petrel pairs dug natural burrows inside the fence but were not known to have laid eggs in their burrows. We continued to employ three social attraction programmes using solar-powered sound systems inside the predator fence: one for Black-footed Albatross, one for Laysan Albatross, and the third for Bonin Petrel and Tristram’s Storm Petrel combined. The Laysan Albatross and Black-footed Albatross systems also included decoys. This season there were 748 documented visits and four breeding attempts by socially attracted Laysan Albatrosses, but none resulted in a fledged chick. Wedge-tailed Shearwaters Ardenna pacifica have established a colony inside the JCNWR predator fence, likely having been attracted by the sound systems. In 2020 we had 18 active burrows fledging 15 chicks. In 2021, Wedge-tailed Shearwater nesting increased with 46 active burrows fledging 43 chicks. When this project began in 2016, there were no seabirds of any kind visiting JCNWR. In 2021, three seabird species bred within the refuge (Bonin Petrel, Laysan Albatross, and Wedge-tailed Shearwater), and a fourth (Tristram’s Storm Petrel) is beginning to visit regularly and hopefully will begin breeding soon. We plan to do one more year of translocations with Tristram’s Storm Petrels and to continue the social attraction and monitor the return and breeding of all species.

The Isla Guadalupe Seabird Translocation Project

A translocated Black-footed Albatross chick exercises its wings beside an adult decoy on Isla Guadalupe

A translocated Black-footed Albatross chick exercises its wings beside an adult decoy on Isla Guadalupe

In collaboration with many partner agencies in the USA and Mexico, and under the Canada/Mexico/US Trilateral Island Initiative, in 2021 we translocated Black-footed Albatross eggs and chicks from Midway Atoll to Mexico’s Isla Guadalupe to create a new breeding colony. Black-footed Albatrosses already forage in the cold waters of the California Current around Guadalupe, which is less likely to be affected by climate change than most other regions of the Pacific. Guadalupe is a large, high island that is protected as a Biosphere Reserve and supports a thriving colony of Laysan Albatrosses.

A Laysan Albatross is about to feed its foster Black-footed Albatross chick on Isla Guadalupe

Photographs from Pacific Rim Conservation

We translocated 21 Black-footed eggs in January and placed them in Laysan Albatross foster nests on Guadalupe, and then in February moved 12 chicks that were raised by hand. Eighteen of the 21 eggs hatched, and all 18 of those chicks fledged. Nine of the 12 translocated chicks fledged, for a total of 27 chicks fledging from Guadalupe in 2021. In January 2022 we translocated 36 more Black-footed eggs to Laysan Albatross foster parents on Guadalupe, of which 35 have hatched. Creation of a breeding colony in the eastern Pacific will increase the breeding range of the species and enhance its resiliency to climate change – as well as adding a new breeding species for Mexico.

From the USA to Mexico: a 2021 translocated Black-footed Albatross fledgling takes to the air on Isla Guadalupe; by ABUN artist Deepti Jain

after a photograph by J.A. Soriano, Grupo de Ecología y Conservación de Islas

US Project Partners: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge (JCNWR), Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, U.S. Navy and Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources.

Mexico Project Partners: Grupo de Ecología y Conservación de Islas (GECI), Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP) and Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO).

Lindsay Young & Eric VanderWerf, Pacific Rim Conservation, Oahu, Hawaii, USA, 17 June 2022

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español