A pair of Campbell Albatrosses displaying on Campbell Island

NOTE: This post continues an occasional series that features photographs of the 31 ACAP listed species, along with information from and about their photographers. Here Peter Moore writes about his experiences with the globally Vulnerable and nationally At Risk - Naturally Uncommon Campbell Albatross Thalassarche impavida. Peter worked for many years as a seabird scientist for New Zealand’s Department of Conservation, most recently in its then Marine Conservation Unit. He is now with the Institute for Applied Ecology in Oregon, USA. See accounts for species so far covered in the series in the Photo Essays section on this website, including Peter’s photo essay on the Southern Royal Albatross Diomedea epomophora.

Peter Moore holds a Campbell Albatross chick for weighing, measuring and banding on Campbell Island, March 1988

The Campbell Albatross breeds only on Campbell Island, one of the sub-Antarctic islands south of New Zealand and is found throughout Australasian waters. The species is similar in appearance to the circumpolar Black-browed Albatross T. melanophris but has honey-coloured irises and broader black margins to its underwings. Adults breed annually and arrive on the island in early August, lay a single egg in late September-early October and fledge chicks in mid-April. Colonies are shared with the less numerous and biennially-breeding Grey-headed Albatross T. chrysostoma.

Close-up of a Campbell Albatross, showing the honey-coloured iris

My first connection with Campbell Albatrosses, or Campbell Island Mollymawks, as we more commonly refer to them in New Zealand, came in 1987-88 when I spent a year on Campbell Island conducting research and monitoring projects for the Department of Conservation. One of our main tasks was to record breeding success of the “mollies” at the “study square” at Bull Rock South. This included banding breeding pairs and their chicks. Although sporadic observations of mollymawks had been made previously, and many thousands of chicks and adults had been banded since the 1950s, this was the first attempt at a more systematic study.

Campbell Albatross adults and chicks at Bull Rock South, Campbell Island, January 1998

So began approximately weekly visits, from October to May, to the Bull Rock South mollymawk colony at the north-east tip of Campbell Island. As you emerge from the scrub behind the colony, you are greeted by the cacophony of thousands of mollymawks calling and squabbling - a sound akin to many dueling chainsaws. The busy city of birds covers many ledges perched above spectacular cliffs. As with all albatrosses, Campbell Albatrosses show wonderful mastery of the wind, soaring gracefully over the waves. Built for speed, however, they are not always able to land very gracefully, and the final run into a colony ledge can be a bit out of control. With spacing between nests determined by pecking distance, any interloper must run the gauntlet of many annoyed birds defending their spot.

A young Campbell Albatross chick, December 1987

A Campbell Albatross chick on its pedestal nest, February 2008

In 1987, we established a set of photo points to monitor changes in the population. Notably, J.H. Sorensen, while stationed on the island with the ‘Cape Expedition’ during World War II, took several photographs of colonies. These have been invaluable for comparison with more recent photos. The 1962 book by Bailey and Sorensen draws heavily on the latter author’s diaries and is a must-read for anyone interested in the wildlife of Campbell Island. A field hut located close to the mollymawk colonies is also named in his honour.

Incidentally, field huts sometimes had a resident pair of Brown or Subantarctic Skuas Catharacta antarctica that would visit us to see what was going on. On one occasion, we conducted a scientific experiment on the dietary preferences of “Mr and Mrs Chook”. During a rigorous set of randomized trials, canned (and expired) Lancashire Hotpot won hands-down over Irish Stew. Very curious birds, if you happen to lie down to rest in the tussock after a hard morning surveying albatrosses, a skua will soon arrive to check out if you have expired.

One of my favourite routes on the island involved a return trip to Beeman Base from Sorensen Hut, near the Bull Rock colonies, via the colonies scattered above the north-western coastal cliffs. Along the way, there are stunning views of the inaccessible Courrejolles Peninsula. The weather can be wild and exhilarating - wind thundering up cliff-faces can sound like an out-of-control train locomotive!

View of Bull Rock North mollymawk colony, 11 December 1942; photograph by J.H. Sorensen

The same view of Bull Rock North in October 1995

Large colonies of Campbell and Grey-headed Albatrosses occur on the slopes of the inaccessible Courrejolles Peninsula on Campbell Island

During several seasons in the 1990s, with the help of several colleagues and volunteers, I conducted censuses of colonies and used counts of nests in photographs to estimate population change. Visiting accessible colonies often entailed walking on steep slopes, and slippery rocks and muddy ledges, which at times felt a little hair-raising.

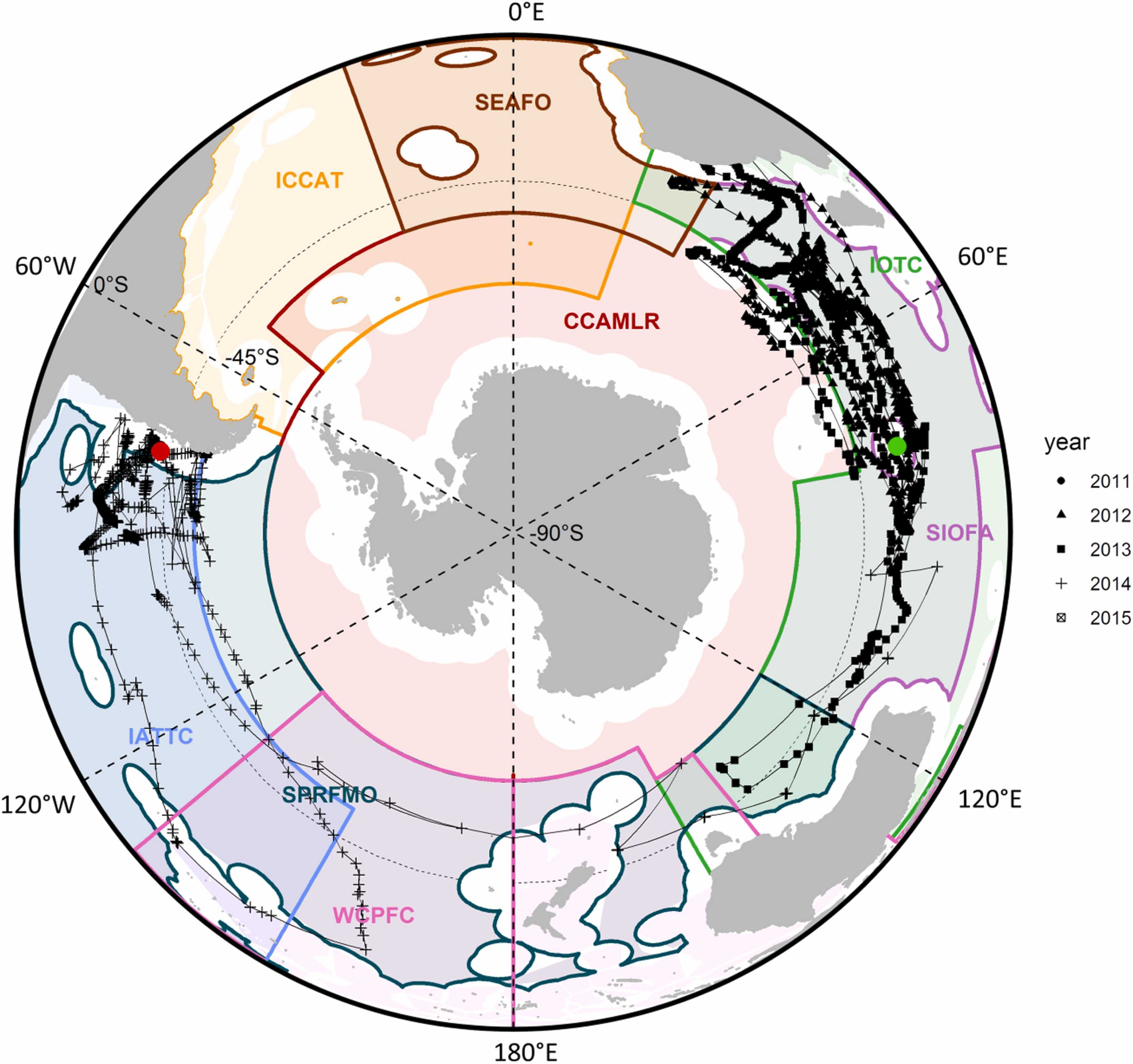

There were approximately 31 000 nests of Campbell Albatrosses in the 1940s, decreasing 22% to 24 600 nests in the 1990s. Campbell Albatrosses often follow fishing vessels and are vulnerable to bycatch. Since the main population decline occurred between the 1960s and 1980s, the peak in tuna longline fishing in the New Zealand region may have had an impact. A new population assessment in 2019 estimated there were 24 300 nests, suggesting relatively little change occurred over the intervening twenty-plus years. In contrast, Grey-headed Albatrosses have continued to decline steadily in numbers on Campbell Island.

There are probably few land-based threats to albatrosses on Campbell Island nowadays - feral cats Felis catus apparently disappeared after domestic sheep Ovis aries were culled in the early 1990s, and Norway Rats Rattus norvegicus were eradicated in 2001. Subantarctic Skuas remain the main predator of seabirds on the island.

Over the years, it was a great privilege to spend time on Campbell Island, and my time with the “mollies” was a special highlight. It feels like a corner of the world that is relatively untouched by humans, yet it is not beyond the touch of climate change. I hope these magnificent birds continue to thrive in the face of a changing world.

Rainbow off the Bull Rock North colony, October 1996

Selected publications:

Bailey, A.M. & Sorensen J.H. 1962. Subantarctic Campbell Island. Proceedings Number 10. Denver Museum of Natural History. 305 pp.

Frost, P.G.H. 2020. Status of Campbell Island and Grey-headed Mollymawks on the Northern Coasts of Campbell Island, November 2019. Whanganui, New Zealand: Science Support Service. 24 pp. Final reports for BCBC2019-03: Seabird population research: Campbell Island 2019/20. Conservation Services Program Reports, Department of Conservation.

Moore, P.J. 2004. Abundance and population trends of mollymawks on Campbell Island. Science for Conservation No. 242. Wellington: Department of Conservation. 62 pp.

Waugh, S.M., Weimerskirch, H., Moore, P.J. & Sagar, P.M. 1999. Population dynamics of black-browed and grey-headed albatrosses Diomedea melanophrys and D. chrysostoma at Campbell Island, New Zealand, 1942-96. Ibis 141: 216-225.

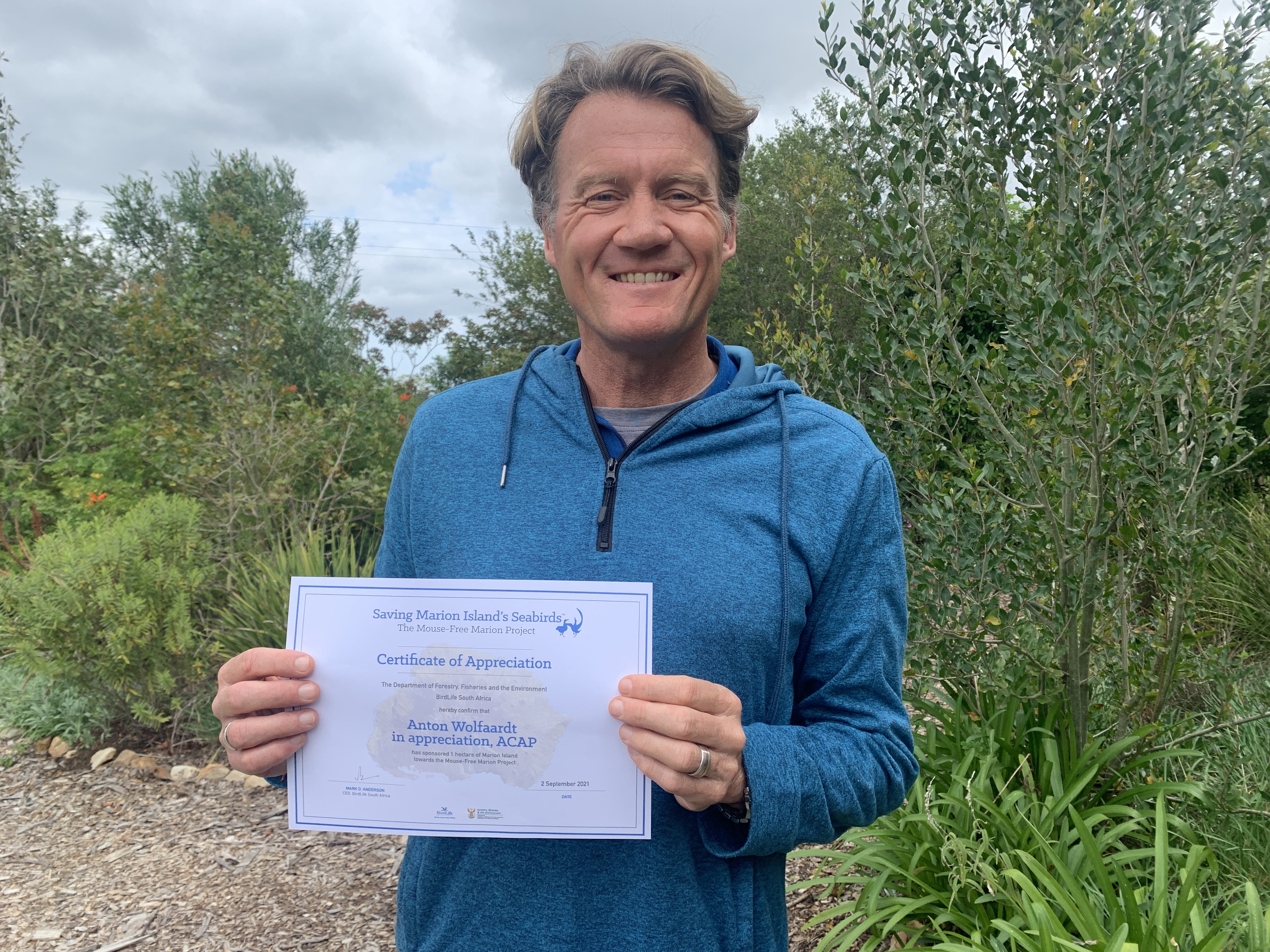

Peter Moore, Institute for Applied Ecology, Corvallis, Oregon, USA, 13 January 2022

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español