A Tristan Albatross stands over its chick, photograph by Peter Ryan

Conservation organisations struggle to directly assist all threatened species, so deciding where to spend limited resources is a common problem. The rate at which a species is decreasing is often a good indicator as to how urgent it is to conserve it.

Albatrosses are among the largest flying birds in the world, and they can get incredibly old. A female Laysan Albatross Phoebastria immutabilis named Wisdom who was first banded >65 years ago is still breeding today. Albatrosses achieve this long life by reproducing very slowly – they often need 5-15 years before they can start breeding. In the largest species, a breeding pair can only raise one chick every two years because it takes almost 12 months for the chick to grow large enough to fly, and parents need a long rest between raising chicks.

This adult Tristan Albatross did not survive attacks by mice, photograph by Peter Ryan

Despite being amongst the largest birds, albatrosses can be threatened by some of the smallest mammals – mice. On several islands such as Marion (South Africa) or Midway (USA), introduced non-native House Mice Mus musculus have started to eat albatross chicks and sometimes even adults. As a consequence, the albatross species breeding on those islands have a low breeding success as chicks are lost to hungry mice.

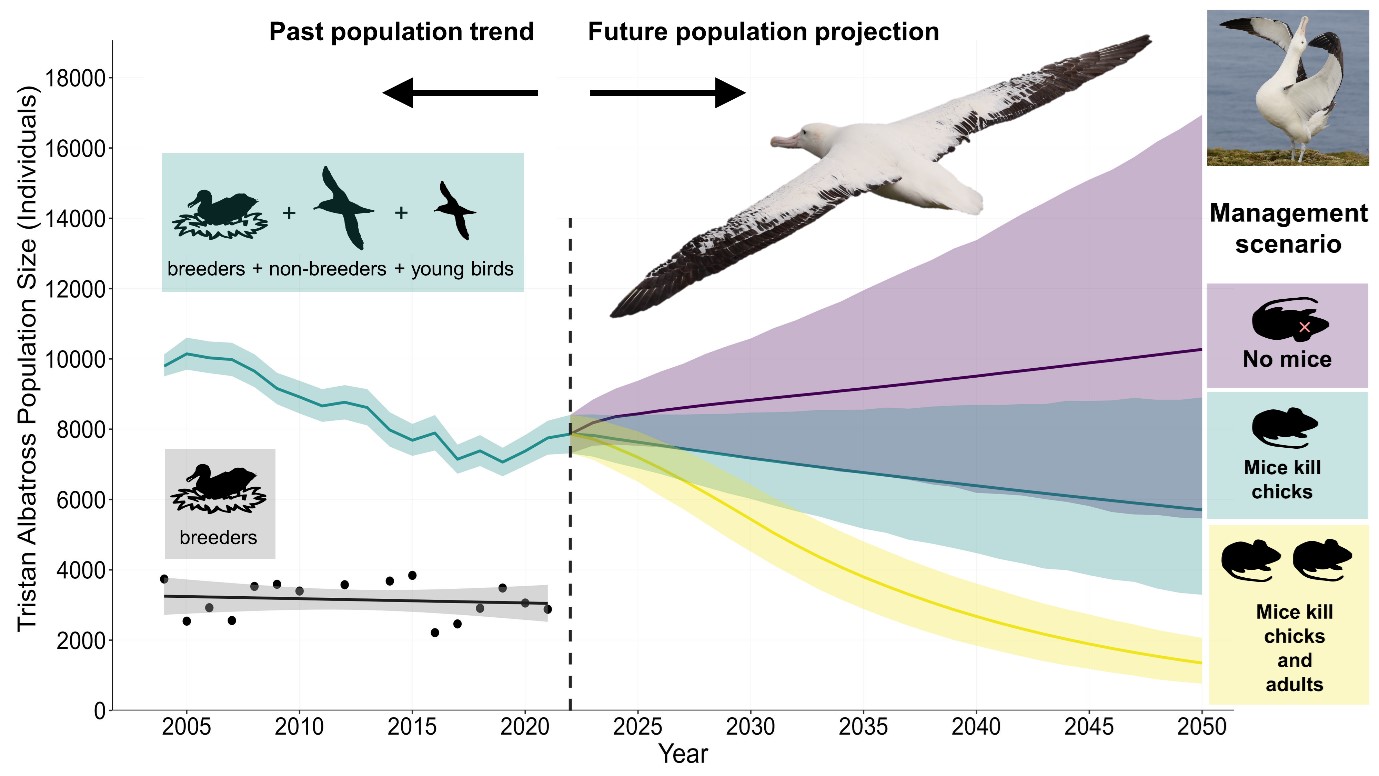

Although this problem has been known for two decades, the consequences of mouse predation have so far been difficult to evaluate due to the long lifespan of albatrosses. For example, the Critically Endangered Tristan Albatross Diomedea dabbenena has lost on average half of each season’s chicks to mouse predation since monitoring began in 2004. Yet, over the same period, the breeding population has remained remarkably stable at ~1500 pairs every year, leaving conservationists puzzled what the impact of mice might be, and whether albatrosses would benefit from an ambitious operation to eradicate mice from their main breeding island.

A new paper published this week in the Journal of Applied Ecology provides a compelling answer. A consortium of researchers funded by the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP) used a sophisticated population model that accounts for all the young albatrosses, and adults taking a break from breeding, that roam the Southern Ocean and therefore cannot be counted by ornithologists. The paper’s authors found that the total population of the Tristan Albatross has in fact decreased by >2000 birds since 2004 – despite the stable number of breeding pairs. Extrapolating 30 years into the future, the researchers further concluded that eradicating mice from their main breeding island would most likely result in a Tristan Albatross population that was two to eight times larger in 2050 than if the mice remained.

Anton Wolfaardt, Project Manager of the Mouse-free Marion Project writes: “This new study is incredibly important for Marion Island, where mice also kill albatrosses. It confirms the importance of eradicating mice on Marion to restore and secure a positive conservation future for the island’s globally important albatross populations.”

The population projections come with large uncertainty though – mostly because it is very difficult to know whether young albatrosses are still alive. After fledging, albatrosses can spend 2-20 years at sea when they cannot be accounted for. This uncertainty renders the estimates of population size somewhat imprecise, and when extrapolating the population 30 years into the future, the range of uncertainty spans several thousand birds. Nonetheless, the new estimates are the most robust yet and provide a deal of new information for guiding management decisions.

Besides the persisting problems of albatross bycatch in fisheries, this study gives us hope that some albatross populations can be restored with technically feasible management actions that can be implemented now if governments honour their commitments under the Convention of Migratory Species and financially support these efforts. Overall, the conclusions from the study support the decision that investing in mouse eradication on islands where mice kill albatrosses is likely to be a highly effective strategy to restore populations of these ocean wanderers.

Read a report of the study in The Applied Ecologist.

Reference:

Oppel, S., Clark, B.L., Risi, M.M., Horswill, C., Converse, S.J., Jones, C.W. Osborne, A.M., Stevens, K., Perold, V., Bond, A.L., Wanless, R.M., Cuthbert, R., Cooper, J. & Ryan, P.G. 2022. Cryptic population decrease due to invasive species predation in a long-lived seabird supports need for eradication. Journal of Applied Ecology doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14218.

Bethany Clark, BirdLife International, Cambridge, UK, 20 June 2022

Español

Español  English

English  Français

Français